Our Bizarre Fascination with How Writers Work

And my Paris Review interview with the great Javier Marías

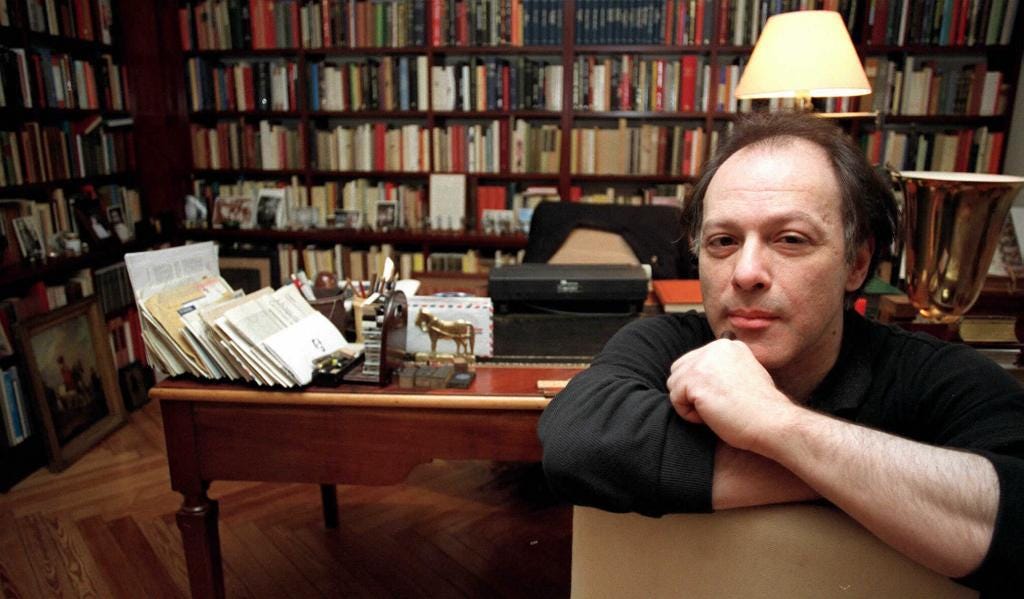

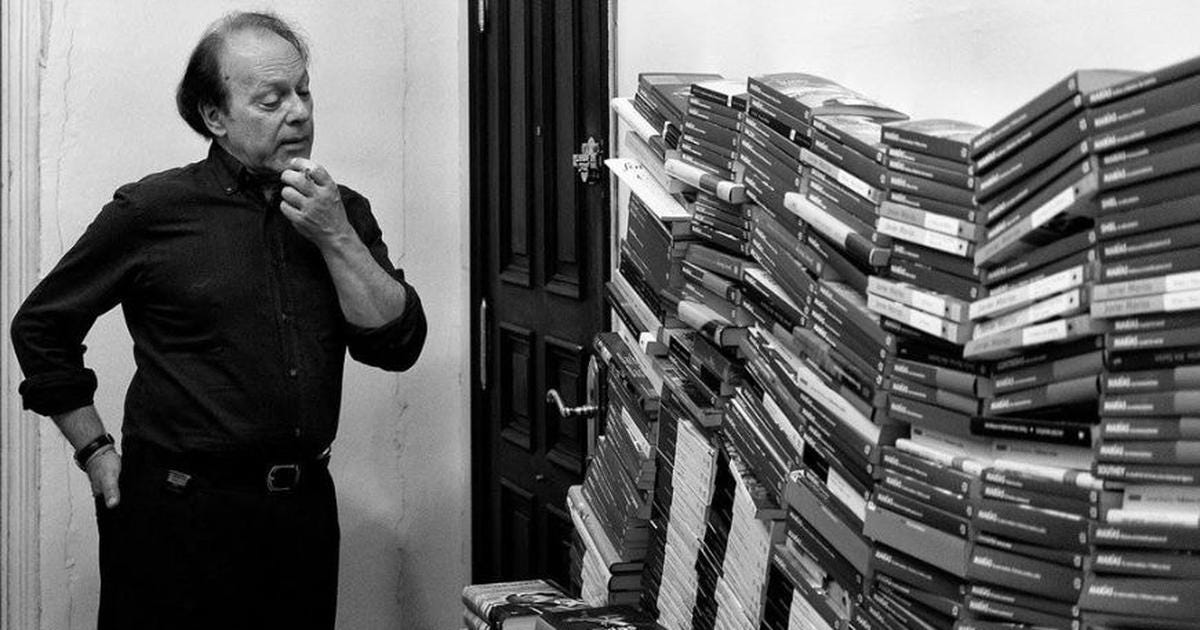

In memory of the Spanish novelist Javier Marías, frequent nominee for the Nobel prize, who passed away in September (2022).

In March 2005, I interviewed the Spanish novelist Javier Marías for one of the Paris Review’s iconic “Art of Fiction” interviews. Marías was then relatively unknown in the United States. Only a small number of readers had read the short profile of him in the New Yorker or the excerpts of his second novel, Voyage Along the Horizon, published in The Believer. But in Europe, particularly in Spain and Germany, he had the celebrity status of a rock star. His books had been translated into over thirty languages and had sold over five million copies worldwide. (He was also the kind of Redonda, an uninhabited Caribbean island—long story.) Earlier that day, while eating lunch at a nearby restaurant, the waitress asked what I was doing in Spain and when I told her that I was in Madrid to interview Javier Marías, she gasped and said, “Sometimes we see him walking down the street!”

At the time, I’d interviewed only one other writer for the magazine—the extraordinary poet Jack Gilbert. I’d spend the next ten years interviewing other others for them: Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Ôe, Pulitzer-prize-winner Marilynne Robinson, National-Book-Award winner Ha Jin, poet laureate Kay Ryan.

I’d already adopted the Paris Review method of interviewing, which my editor Philip Gourevitch had passed on to me. (I never had the chance to meet the magazine’s iconic editor George Plimpton, who died in 2003.) Gourivitch, via Plimpton, emphasized the importance of being knowledgeable enough about her subject’s work to know what not to ask. In preparation for this interview, I had spent three months reading all eleven of Marías’s novels (two in Spanish with the help of a translator); his two collections of short stories; his newspaper column, which runs weekly in El País; reviews of his work; and every interview with him that had been published in English and Spanish (again, with the help of a translator).

The goal was to get them to talk about their work in ways they’d never done in another interview, but it wasn’t to get analytical about it. That was for critics, whom Plimpton started publishing author interviews in 1953 to defy. Craft talk, as it became known, included an author’s work habits, techniques, and process. Several of the magazine’s anthologies have work in the title: Writers at Work Around the World, Women at Work, Poets at Work. In the best Paris Review interviews, authors “talked shop,” sure, but what we really want to know is the nuts and bolts. Quintessential Paris Review questions have now become clichés—Do you write with a pencil or a typewriter? Do you write in the morning or at night?—but were relatively new for much of the twentieth century. These questions have lasted—how long a writer spends writing each day, plus when and how—because we believe they hold some sort of map to authorial brilliance.

Marías’s agent had informed me that Marías typically wrote between eleven at night and two in the morning. This was a juicy nugget of information. Because he didn’t wake until two in the afternoon, our interview sessions would have to take place at six in the evening.

When I arrived at his apartment just off the Plaza Mayor in Madrid, the doorman, an elderly Madrileño, ushered me upstairs. Marías answered the door and politely invited me inside. He had dark circles under his eyes and what can only be described as bed head.

He lit a cigarette. Speaking in English, which he’d become fluent in while lecturing on Spanish literature and translation at the University of Oxford, Marías explained that Orson Welles’s Othello had been on television at three that morning and he hadn’t gone to bed until six am.

He squinted apologetically and took a drag. After a moment, he quietly mentioned that his father had passed away a few months earlier. “I sleep badly,” he said.

Marías gestured for me to sit on a puffy blue chair. As he sat on the couch, his eyes brightened. He described at length how pleased he was to have been chosen as the subject for a Paris Review interview. He’d read them, of course—hadn’t every writer? I settled into the chair and waited for him to continue. He looked at me sheepishly.

Through the haze of cigarette smoke, he said he had read the Paris Review interview with Vladimir Nabokov many times.

I didn’t ask but had he also read them in search of some magical equation—x number of hours per day standing up (Hemingway) and writing with a pencil equals literary success?

Does knowing that Georges Simenon typically completes his novels in ten days help us produce our own work? Or that Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene committed to writing 500 words each day? Or that Nelson Algren had no set routine nor felt the need for one but typically worked best, or most frequently, at night and used a typewriter?

Paris Review interviews are different from other magazines’ and websites’ interviews. The author and interviewer meet over several sessions. (Marilyn Robinson and I had eight sessions.) The interviews are then edited to read as a single conversation. It’s a lot.

On the third day I interviewed Marías, he stubbed out his cigarette, popped up, went to the kitchen, and returned with a thick bar of dark chocolate. After offering me some, he ate a few squares—like a mountaineer in need of an energy boost—and went on talking.

By nine o’clock, Marías’s energy started to fade. He said he’d promised to meet friends at the corner bar to watch fútbol. As he showed me to the door, he seemed exhausted. It was an expression of tiredness I’d seen on other interviewees’ faces—the kind that comes from talking about oneself, one’s work, and one’s habits for too long.

I wonder if we can read too much about other writers’ habits, risking not establishing our own. We constantly wonder whether we’re ever writing enough or in the right way. The result, of course, is a sense of inadequacy that makes writing seem “hard” instead of just a job.

The Paris Review interviews taught me more about writing than my M.F.A. program did. They’re magical, full of “craft talk” about learning to write round, lush characters (E.M. Forster) or how a book finds its own plot through the writing of it (Nelson Algren, Lawrence Durrell, Henry Green, and Aldous Huxley).

But maybe the work—the habits—can only be discovered within each of us without influence.

Or not.

Stay tuned for next week’s post on self-discipline.

And please read all of Javier’s novels. A Heart So White (Corazon tan blanco) and the Your Face Tomorrow (Tu rostro mañana) trilogy are just some of my favorites. His novels make these incredible departures from the primary storyline, yet you never feel dissatisfied by the digressions. They’re part of the whole.

If you feel like you’re flailing around on Substack and not getting any traction, For more on this, book a meeting! Each 30-minute Zoom meeting is the fastest, most efficient way I can help you succeed on Substack.

Book a meeting with Writers at Work with Sarah Fay

After working with me, writers have seen their Substacks double or triple in subscribers, increase in real engagement, and been chosen as Featured Substacks, and, most importantly, they’ve found purpose in their writing and direction in their careers.

I want this for all of us. You won’t find this level of mentoring or expertise anywhere else. My guidance is all based on the advice Substack gave me.

Find out more by reading what the writers who’ve worked with me say here or book a meeting here.