Get all that Writers at Work has to offer, including posts on strengthening your writing habits and workshops on mastering the art and business of being a creative writer on Substack. Become a free or paid subscriber. Your writing and writing career are worth it.

There’s a rumor going around that new subscribers to serial novels and memoirs drop off after five “chapters.” (Remember that serializations have installments, not chapters. It’s an important distinction. Read more about chapters versus installments here.)

The assumption is that—despite the presence of a synopsis—readers don’t want to start in the middle because they don’t know what’s happening.

Not so.

The Synopsis According to Boz

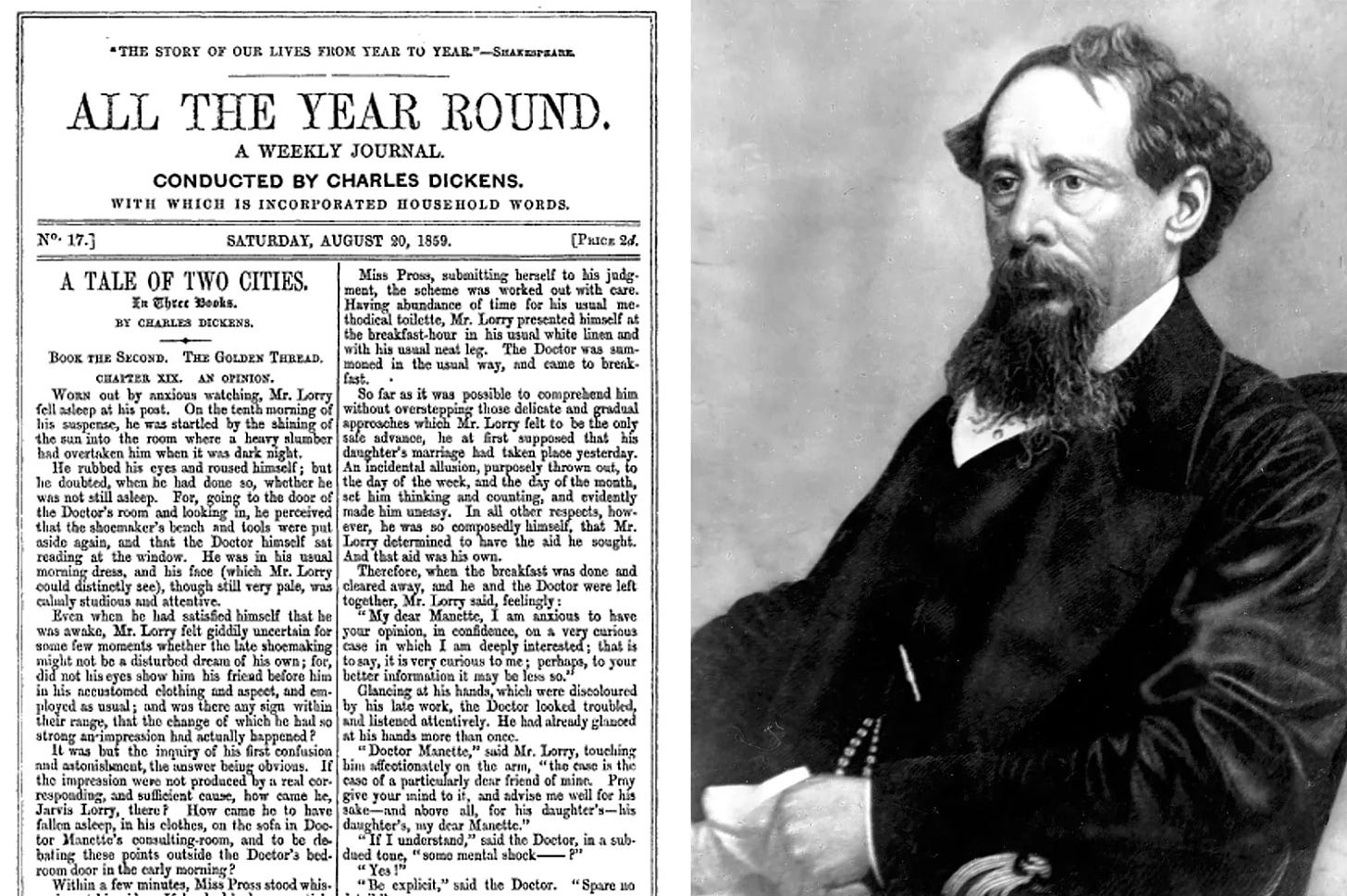

People love to reference Charles Dickens’s serialized novels, but few seem to have actually read or studied them or know what they can teach us. No one had a problem keeping up with or joining the serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop or Little Dorrit or Bleak House. And those were long novels (Bleak House clocks in at a stunning 370,000 words) with complicated plots and way too many characters.

Dickens’s novels were also serialized in print. If you missed an issue, too bad. You had to physically seek out a copy of the missed issue, which could be sold out. (All we have to do is go on the Substack app.)

Most importantly, Dickens used no synopses. None.

Yet Victorian readers waited for each installment with bated breath and joined mid-serialization. The Pickwick Papers, one of Dickens’s first serializations, didn’t sell until installment number 4 and then it sold 40,000 copies.

Yes, it was a different time period (people love to say that), but there was a lot going on back then, too.

Dickens managed this because he knew how to write installments that hooked and captivated readers and then left them hanging. Captivated means he didn’t make the reader do the work. Despite Dickens’s convoluted plots and abundance of characters, readers could pick up the serialization at any point and be delighted and gripped by that part of the story. (Note: That doesn’t mean he wrote standalone pieces or short stories. In fact, his installments included several chapters.) He made it so that readers could discern what was happening and who the characters were from the context.

Everything You Think You Know About Writing a Synopsis May Be Wrong

Three principles should guide you in your approach to the synopsis—if you include one: