Subscriber-Worthy Storytelling

🎧 Listen to the podcast version:

Many Substack writers are on here to share their life experiences. But if you want to tell stories about your life in a way that enthralls readers, you need to know narrative. To know narrative, you need to know plot.

It seems like we should naturally be able to write gripping narratives. We tell stories all the time, don’t we? All those delightful Facebook posts and conversations with friends?

No, we write and tell anecdotes: This happened and then this happened and then this happened…. No plot.

There’s a good reason for this: Our lives are anecdotal and aren’t interesting until we plot them: This caused this to happen and then I felt this is how we make meaning.

The same is true for many Substack writers. They don’t tell stories, they share (dull) anecdotes, thinking they’re stories.

To engage subscribers, especially paying subscribers, we need to make our personal stories (a.k.a. short-form memoir, narrative essays) enthralling—as in I-can’t-wait-to-read-next-week’s-post enthralling.

What you need to know

Anecdotes aren’t narratives; they’re very long Facebook posts.

Narratives keep subscribers reading.

Narratives have a plot.

Plots abide by one rule: “Nothing interesting happens in heaven.” —Charles Baxter

Plot!

Without a plot, readers aren’t interested. The British novelist E.M. Forster said a writer’s mastery of plot determined his success as a novelist.1

But don’t we instinctively know how to plot? All those Netflix binges and novels? All those Substack posts people liked? Haven’t they taught us all we need to know?

No.

The only model you need

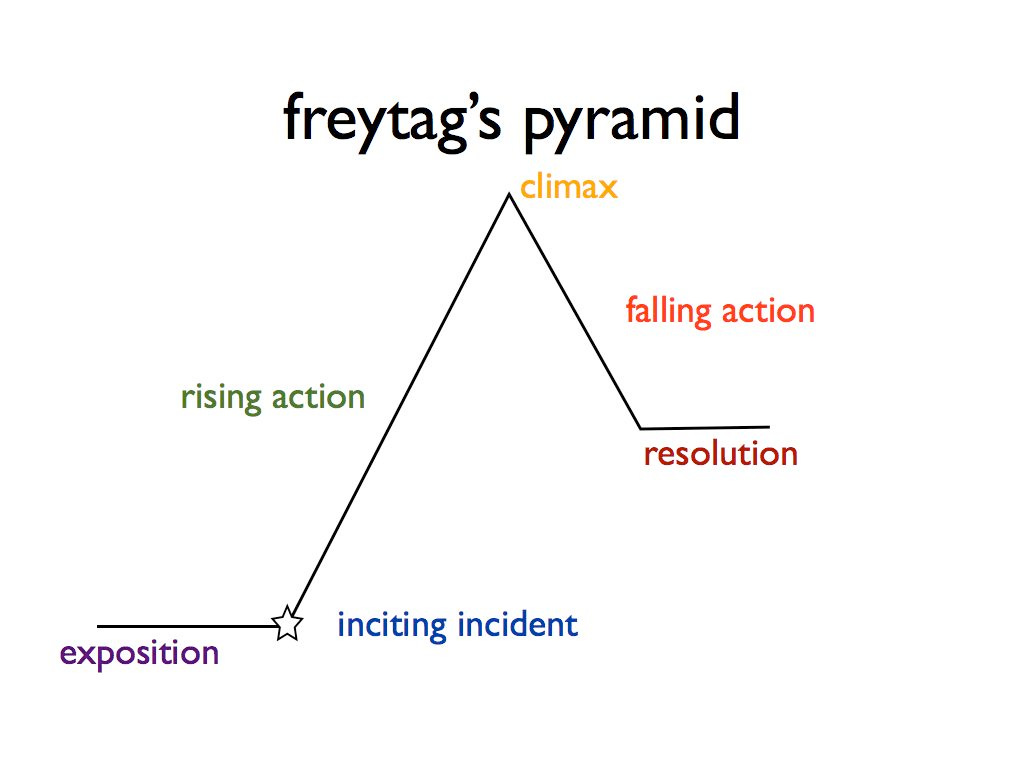

Many, many, many theories about plot structure in narrative abound. It doesn’t matter if there are nine basic plots or seven or seven hundred. Books on story structure and fancy devices based on literary theory are wholly unnecessary. The only technique you need to master is Freytag’s triangle/pyramid.

(It’s often referred to as a pyramid, but that’s woefully inaccurate—more on that in the narrative essay workshop.)

Freytag’s triangle is gold to a writer. It works—and it taps into our evolutionary instincts as storytelling animals. No need to get complicated and originality is overrated.

Don’t listen to anyone who tries to give you any more skills until you’ve mastered this:

Exposition=life as it was

The inciting incident=the moment everything changes

Rising action=three (or more or fewer) events during which you’re prevented from getting what you want (this tug=tension)

The climax isn’t a big battle or even exciting. It is a moment of high tension because you’re faced with a dilemma

The falling action=when things are at their worst because any choice we make has a negative effect or cost.

The resolution isn’t happiness and perfection! Our lives never are. No neatly tied bows, please! Everything comes at a price. The resolution has to be a hard-won good thing during which something was lost—or, in a tragedy, all-out loss.

Every great traditional narrative can be plotted using this structure, from Cinderella to James Joyce’s Ulysses to “Star Wars.”

The exclusive prompt and examples below are the keys to putting this into practice.

✨ Become a paid subscriber to access both. Commit to one year with my guidance and get the discounted annual subscription. You, your writing, and your career are worth it.