Get all that Writers at Work has to offer, including posts on strengthening your writing habits and workshops on mastering the art and business of being a creative writer on Substack. Become a free or paid subscriber. Your writing and writing career are worth it.

Generally, there are two types of writers: the first believes in art for art’s sake; the second thinks writing should engage with and change the world. Often these are thought of as mutually exclusive.

The second type—writers who use their novels and memoirs to build awareness and right wrongs—often meets the criteria for the social novel or social justice memoir.

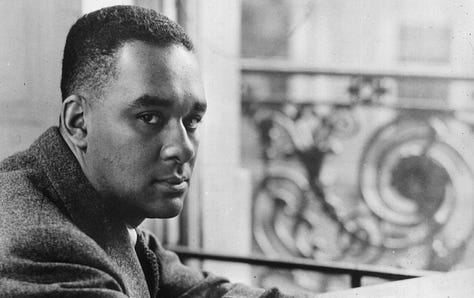

The social, or protest, novel employs a narrative specifically to address social, economic, environmental, or political issues. Novelists as diverse as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Richard Wright, Elizabeth Gaskell, Charlotte Brontë, Tom Wolfe, Yukio Mishima, Benjamin Disraeli, Ayn Rand, Leo Tolstoy, George Eliot, and Theodore Dreiser have written them. In France, they’re called romans à thèse—thesis novels—a form embraced by Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Émile Zola, Albert Camus, and others.

Social justice memoirs began in the eighteenth century and have had a resurgence as of late. The first slave narrative (and bestseller) is said to be the Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or, Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (1789) by Olaudah Equiano. Others, like Maya Angelou, Bryan Stevenson, Margo Jefferson, Kiese Laymon, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Roxane Gay have written social justice memoirs though not all of these writers would call them that, per se.

How Serialization Can Change the World

Many social novels and memoirs first came into the world as serials. Serialization has a special power. The very nature of it—installments doled out, interrupting readers’ lives several times a week or once a week—penetrates a reader’s consciousness in a more affecting and sustained way than a single volume in one sitting can. Bingeing Netflix-style on a novel or memoir can cause it to leave our minds as quickly as it entered.

Serial novels and memoirs in the service of social justice have enacted real change. Slave narratives and memoirs and, to some extent, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, likely led to emancipation; Charles Dickens’s novels instigated new laws to address economic inequality and institutional corruption; and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle gave us the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

When done well, social novels and social justice memoirs can be life changing. Not everyone finds social novels the least bit admirable, including James Baldwin, who, in his essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” rips Uncle Tom’s Cabin to shreds. Baldwin’s essay is excellent and well worth reading.

Obviously, I disagree with Baldwin. Read on. I take you through four examples of serialized social justice.

1. Slave Narratives and Memoirs

These memoirs, told and written by those who’d experienced bondage and brutality, forced at least some of the reading public to face the gravity of what was happening, giving voice to those who deserved it most.

Among other slave narratives, “Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave” appeared in the abolitionist newspaper The Emancipator in 1838. The man featured, a freed slave, goes unnamed. He tells his story to a journalist who regrets that the transcription lacks “that earnestness--that depth of feeling which gave it life, as it was uttered by one, who himself had seen all, and felt much of the reality.” The violence the man suffered and all he had to endure to free himself is unfathomable yet undeniable because the words are right there on the page.

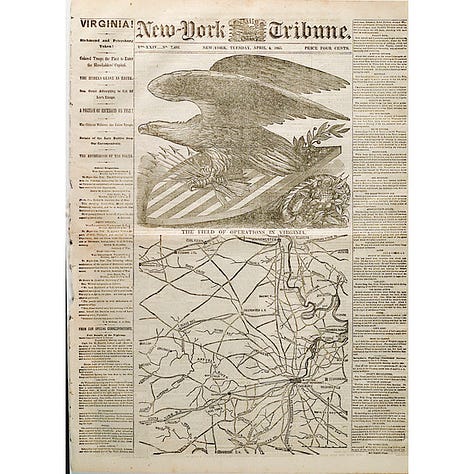

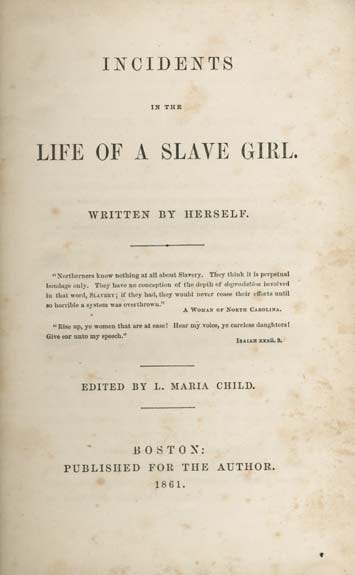

Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Written by Herself was partly serialized in the New York Daily Tribune in 1853.

The editors intended to run her entire story, which begins with the years she spent fending off the sexual advances of her slaveholder, follows her escape and the seven years she spent in hiding in a three-foot-by-seven-foot attic crawl space (that’s not a typo—seven years!), and ends with her eventual freedom in the North. But the New York Daily Tribune ended the serialization when readers objected to the sexually explicit content.

Having been denied the opportunity to appear in serial form, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Written by Herself was published as a single volume. Any book authored by a slave had to be “edited” by a white person supposedly to lend the story “credibility.” Jacobs’s memoir appeared with Lydia Maria Child’s name on the title page. Child was an abolitionist and fiction writer. People assumed Jacobs’s story was a novel by Child, the racist notion being that an ex-slave couldn’t write as eloquently as Jacobs did.

Jacobs died without receiving credit for her work. It wasn’t until the 1970s (also not a typo) that the historian Jean Fagan Yellin discovered Jacobs’s papers and proved that Jacobs was the author.

2. Nearly All of Charles Dickens’s Novels

Those who see Dickens only as a delightful storyteller miss out on his true aim: social reform. For Dickens, a novelist’s place was in the world, not at a literary remove. As he wrote to Wilkie Collins in 1858, “Everything that happens […] shows beyond mistake that you can’t shut out the world; that you are in it, to be of it; that you get yourself into a false position the moment you try to sever yourself from it.”

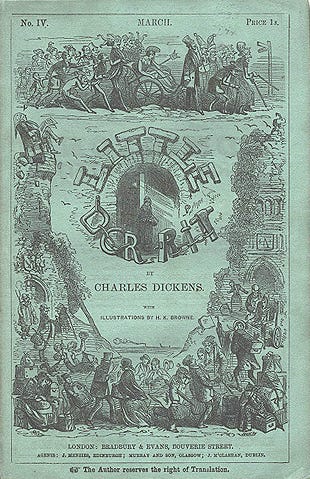

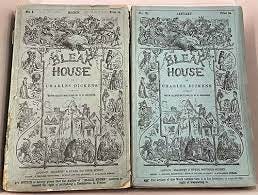

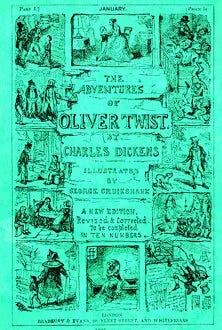

His novels bristle with social commentary. They condemn child labor (A Christmas Carol), economic inequality (Oliver Twist, Hard Times), the environmental effects of urbanization and industrialization (Bleak House), inhumane debtor’s prisons (Little Dorrit), and England’s corrupt Magisterial court system (Bleak House).

Dickens changed the public consciousness. Because his fictionalization of these issues appeared in serial, he reached more of society and had greater influence. Only the upper classes could afford books whereas the working and middle classes could buy magazines. His novels instigated legal reforms on many issues.

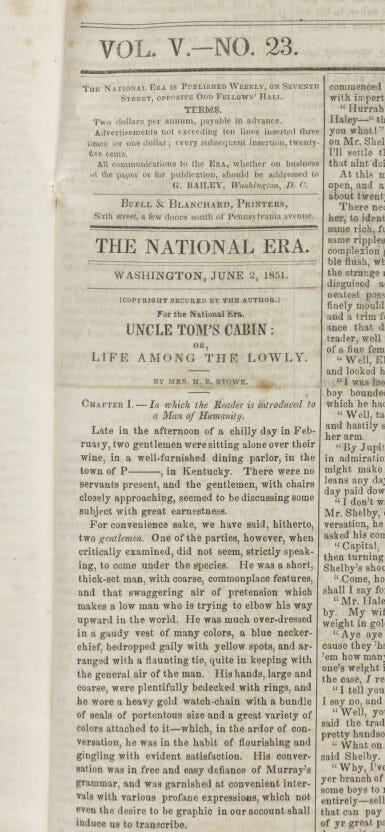

3. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly

When Abraham Lincoln met Stowe in 1862, he supposedly said she was “the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war”—i.e., the Civil War. She wasn’t, of course, but Uncle Tom’s Cabin was, as Putnam’s Monthly Magazine put it, a “phenomenon.”

The novel tells the story of two slaves (Tom and Henry), one of whom escapes to freedom and the other who doesn't. It’s practically unreadable today; Stowe’s racism is glaring. Despite her best intentions, she was a product of her time.

The novel's flaws don't diminish its impact. It was said to have shocked whites in the North and shamed (some) whites in the South.1

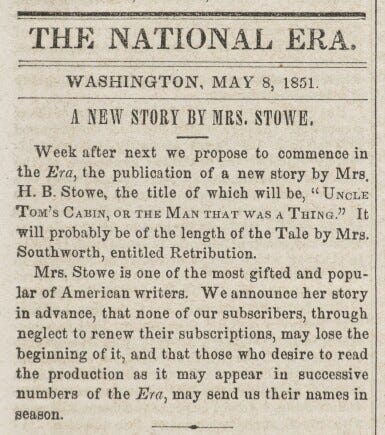

Had Uncle Tom’s Cabin not first been serialized in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era, it might not have been published. The forty-one installments of the novel grew the National Era’s subscriber base by 26 percent. An estimated 50,000 people read it in serial form. There was no intention to publish it as a single volume, but its sales prompted the publisher John P. Jewett and Company to release it in two single volumes.

It sold 3000 copies on the first day and 300,000 in the first year of publication (1852). Stowe became the most famous “authoress” in America and Uncle Tom’s Cabin the bestselling novel of the nineteenth century.

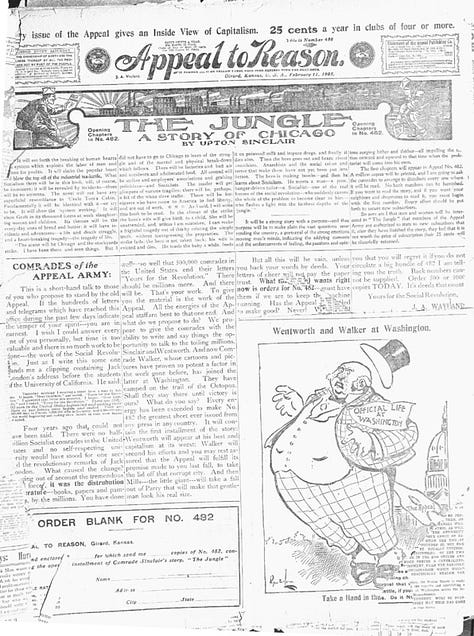

4. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle

Like Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Stephens, and others, Sinclair was a “muckraker” journalist who devoted his life to exposing corruption. Sinclair wrote The Jungle (1906) to educate the public about economic inequality and the abhorrent treatment that immigrants faced in this country.

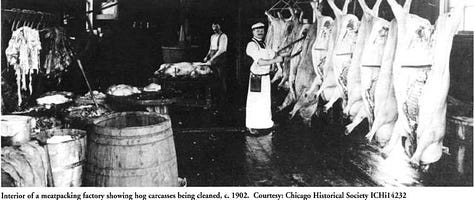

It’s a heartbreaking depiction of the Rudkus family, Lithuanian immigrants, who are swindled and mistreated by pretty much every American they come in contact with.

The Jungle appeared weekly in Appeal to Reason, a socialist-leaning newspaper, between February and December 1905 and was published in a single volume in 1906. Sinclair had hoped the novel would spark reform of immigration policies and recruit Americans to socialism’s cause.

That’s not what happened. The immigration-rights aspect of the novel was lost on readers entirely; instead, they were troubled by the scenes of the members of the Rudkus family who are forced into grueling work at a meat-packing plant. Suffering immigrants didn’t bother readers, but the conditions in which their food was made did.

Sinclair saw the novel as a failure: “I aimed at the public’s heart,” he wrote, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Still, the novel did enact change. Public outrage spurred a congressional investigation that led to the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, from which the Food and Drug Administration was born.

How to Serialize Social Justice Now

Today, when so many Americans feel confused and despairing at inequality in our country, the social novel or social justice memoir may have a place, particularly in serial form.

The genre requires a light touch. Many of the works listed above were derided as didactic, not just by Baldwin but by others who saw them not as literary works but as “pamphleteering.” Some would argue didacticism is a requirement of the form, but it likely wouldn’t work today.

They’re worth the effort. I love escaping into a book, but I also want to learn from them.

Be the writer you’re meant to be on Substack

Book a meeting

I can save you years of flailing around on Substack, trying to figure out the platform, and not getting any traction. I’ve seen the most amazing results in the Substack writers I’ve worked with: journalists, psychologists, people in tech, culture writers, creative writers of every genre, healthcare practitioners, scientists, those just starting out, and those that have been on Substack for years.

Each 30-minute Zoom meeting with me gives you an expert set of eyes on your Substack. I help you

focus your Substack,

figure out how your talents and expertise work best on this platform,

up-level your writing,

use Substack to leverage your career and achieve your goals, and (of course)

increase your subscribers.

I share with you the advice the folks at Substack gave me and all my experience as an author at HarperCollins; the creator of two bestselling, featured Substack publications; a former advisory editor at The Paris Review; and a creative writing professor at Northwestern University.

Book a 3-meeting package for $25 off:

Or book a single meeting:

Book a meeting with Writers at Work

Critics objected to the novel’s content and composition early on and never stopped. Upon publication, it was attacked as being mere fiction driven by emotion and unrepresentative of facts. This defensive response was a way of denying the pure evil of slavery. Since then, it’s been derided as an unliterary, preachy pamphlet, which was Stowe’s intention.

With regard to the need for a light touch it may be relevant to quote George Eliot's dictum 'Never wrap a sermon in a novel' ( or something close to that) although the social aspects in all her novels stand pretty clear. Perhaps what she meant was that the 'issues' had to be intrinsically valid for the lives of her characters, as was the stigma of illegitimacy for the empty headed Hetty Sorrel, driven to the murder of her baby in Adam Bede. So I suppose the 'guide' towards getting the balance right, is the character and her/his situation must take the rein and the hand that guides the story have a very light touch? Or be absent altogether to let the issue emerge naturally.

Or, a possible 3) be caught by prevailing mores into actions that seem to offer no choice at all, but which define the journey of self determination, maybe catastrophic, maybe liberating? That might focus attention on issues of injustice, or narrowness without ever addressing them explicitly?